Apart from having a unique name, chemical elements are also identified by a unique symbolic representation. Chemical symbols are one or two letters from the Latin alphabet, but can be three letters when the element has a provisional name. Chemical symbols are written with an uppercase first letter, followed by zero ore more lowercase letters.

Earlier chemical symbols stem from classical Latin and Greek vocabulary. For some elements, this is because the material was known in ancient times, while for others, the name is a more recent invention. For example, He is the symbol for helium (New Latin name; not known in ancient Roman times), Pb for lead (plumbum in Latin), and Hg for mercury (hydrargyrum in Greek). Some symbols come from other sources, like W for tungsten (Wolfram in German; not known in Roman times).

Provisional symbols assigned to newly or not-yet synthesized elements use 3-letter symbols based on their atomic numbers. For example, Uno was the temporary symbol for hassium (element 108) which had the temporary name of unniloctium.

In Chinese, each chemical element has a dedicated character1, usually created for the purpose. However, Latin symbols are also used, especially in formulas.

Assignment

To get rid of the fact that there isn't always a direct connection between the name of a chemical element and its symbolic representation, we have decided to use a systematic way to assign a new symbol to each chemical element. These are the selection criteria we have already agreed upon:

-

each symbol must start with an uppercase letter, followed by zero or more lowercase letters

-

symbols should be formed by discarding letters from the name of the chemical element (without making a distinction between uppercase and lowercase letters, but taking into account the order of the letters as they occur in the name of the chemical element)

This still opens the possibility to derive many candidate symbols from the name of a chemical element. The following additional selection criteria are still under discussion:

-

all chemical elements should have fixed-length symbols (for example two-letter symbols)

-

of all candidate symbols, preference is given to the one that comes first/last alphabetically

In order to help selecting new symbols for the chemical elements, you are asked to:

-

Write a function isvalid that takes the symbolic representation (str) and the name (str) of a chemical element. The function must return a Boolean value (bool) that indicates whether the given symbol meets criteria (1) and (2) for the chemical element with the given name. The function also has an optional third parameter length that may take an integer $$n \in \mathbb{N}_0$$ (int). If a value is explicitly passed to the parameter length, the Boolean value returned by the function should in addition also indicate whether the given symbol has length $$n$$ (cfr. criteria (3)).

-

Write a function symbols that takes the name (str) of a chemical element. The function must return a set containing all two-letter symbols (str) that meet criteria (1) and (2). These are all combinations of any two letters in the name of the element, where the first letter occurs before the second letter in the name, with the first letter converted to uppercase and the second to lowercase.

-

Write a function preference that takes the name (str) of a chemical element. The function also has an optional second parameter last that may take a Boolean value (bool, default value: False). The function should return the two-letter symbol (str) that meets criteria (1) and (2), and that comes first (parameter last has value False) or last (parameter last has value True) alphabetically of all two-letter symbols that meet these criteria.

Example

>>> isvalid('Zer', 'Zeddemorium')

True

>>> isvalid('Zer', 'Zeddemorium', 2)

False

>>> isvalid('di', 'Zeddemorium')

False

>>> symbols('Iron')

{'Ir', 'Io', 'In', 'Ro', 'Rn', 'On'}

>>> symbols('Neon')

{'Eo', 'Nn', 'No', 'En', 'Ne', 'On'}

>>> preference('Iron')

'In'

>>> preference('Iron', last=True)

'Ro'

>>> preference('Neon')

'En'

>>> preference('Neon', True)

'On'

Epilogue

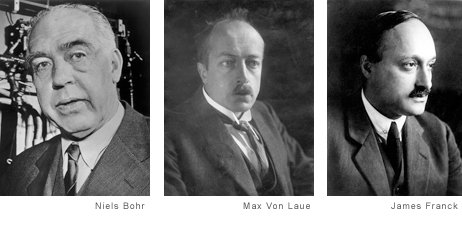

When Hitler's army marched into Copenhagen, Niels Bohr2 had to decide how to safeguard the Nobel medals of James Franck3 and Max von Laue4, which they had entrusted to him. Sending gold out of the country was almost a capital offense, and the physicists' names were engraved on the medals, making such an attempt doubly risky. Burying the medals seemed uncertain as well. Finally his friend — the Hungarian radiochemist George de Hevesy5 — invented a novel solution: he dissolved the medals in a jar of aqua regia6, which Bohr left on a shelf in his laboratory while he fled to Sweden.

When he returned in 1945, the jar was still there. Bohr had the gold recovered, and the Nobel Foundation recast it into two medals.

Chemist Hermann Francis Mark7 also found a clever way to escape Germany with his money: he used it to buy platinum wire, which he fashioned into coat hangers. Once he had brought these successfully through customs, he sold them to recover the money.