From the 1850s until his death, August Kekulé (1829-1896) was one of the most prominent chemists in Europe, especially in theoretical chemistry. In 1856 he became Privatdozent at the University of Heidelberg. In 1858 he was hired as full professor at the Ghent University, then in 1867 he was called to Bonn, where he remained for the rest of his career.

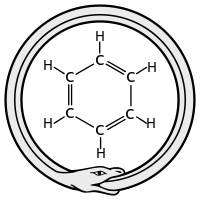

Kekulé was the principal founder of the theory of chemical structure. His most famous work was on the structure of benzene. In 1865 he published a paper in French — he worked at Ghent University, which was still a French-speaking university at the time — suggesting that the structure contained a six-membered ring of carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds. The next year he published a much longer paper in German on the same subject.

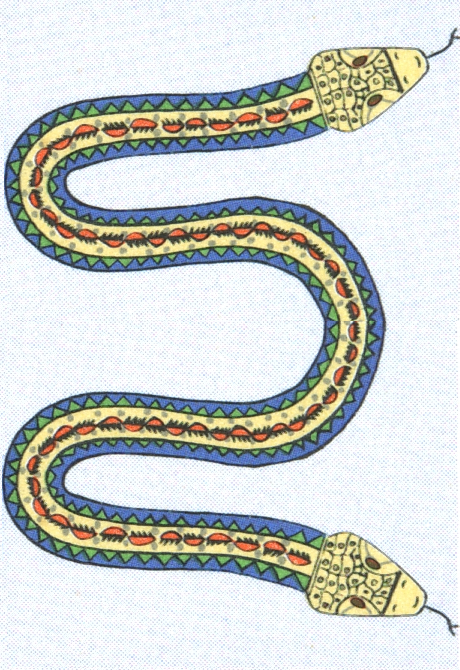

This new understanding of benzene — and hence of all aromatic compounds — proved to be so important for both pure and applied chemistry after 1865 that in 1890 the German Chemical Society organized Benzolfest, an elaborate appreciation in Kekulé's honor, celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of his first benzene paper. At this meeting, Kekulé spoke of the creation of the theory. He said that he had discovered the ring shape of the benzene molecule after having a reverie or day-dream of a snake seizing its own tail — this is an ancient symbol known as the Ouroboros. This vision — that was later called the Ouroboros dream — came to him after years of studying the nature of carbon-carbon bonds. This is how he described the eureka moment when he realized the structure of benzene:

I was sitting, writing at my text-book; but the work did not progress; my thoughts were elsewhere. I turned my chair to the fire and dozed.

Again the atoms were gamboling before my eyes. This time the smaller groups kept modestly in the background. My mental eye, rendered more acute by the repeated visions of the kind, could now distinguish larger structures of manifold conformation: long rows, sometimes more closely fitted together; all twining and twisting in snake-like motion. But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes.

As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis.

Opinions about the truth of this story are devided. According to non-believers, Kekulé has retrospectively invented this dream, or at least exaggerated its role, to hide the fact that French chemist Laurent discovered the structure of benzene before him.

Assignment

In this assignment we look for words with snake-like properties. Based on these properties, we have named the different classes of words after three mythical snakes: Ouroboros1, Tsuchinoko2 and Amphisbaena3.

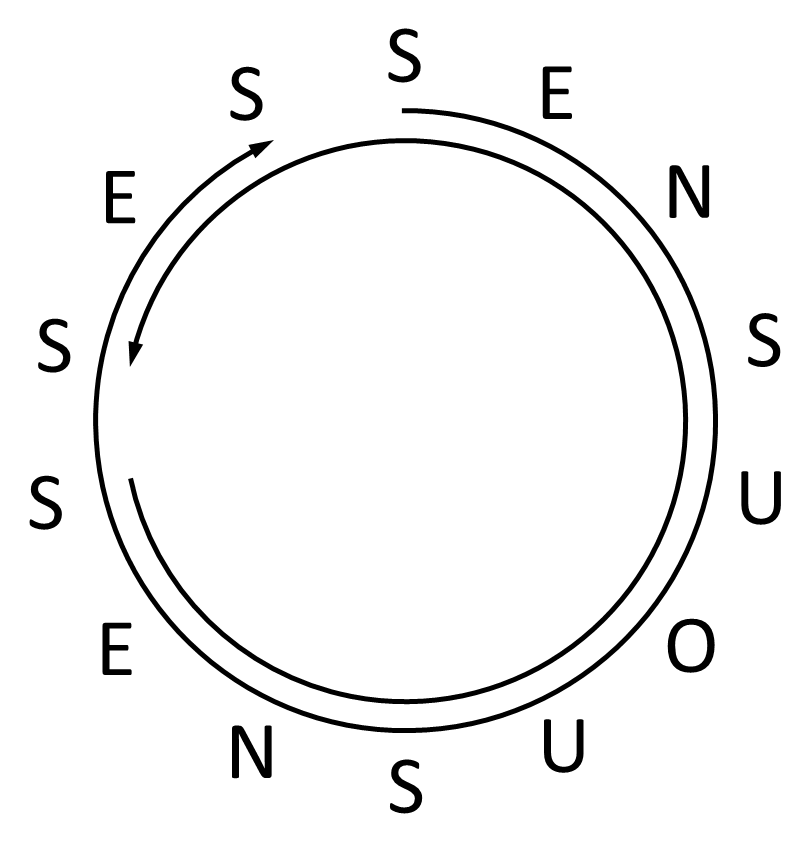

An ouroboros is a word that — when written in a circle — can be read both clockwise and counterclockwise. By definition, palindromes (words that read the same from left to right and from right to left) are never ouroboros. The figure below shows that the English word SENSUOUSNESSES is such a circular palindrome.

One technique to determine whether or not a given word is an ouroboros is to write the word twice in a row, and find out if it contains the reverse word. But not at the start or the end, otherwise the word is a palindrome.

The tsuchinoko of a word or a sentence is the number of letters (other characters are ignored) that occupy the same position as in the alphabet. In the word ARCHETYPICAL, five letters occupy the same position as in the alphabet — A is first, C third, E fifth, I ninth and L twelfth. In the remarkable sentence

A bad egg hit KLM wipers two ways.

composed by Ross Eckler, fully 16 of 26 letters occupy their alphabetic positions. In determining the positions we only take into account the letters, the other characters in the sentence are ignored.

A word is an amphisbaena if the first half and the last half of the word contain exactly the same letters, but not necessarily in the same order. In case the word has an odd number of letters, the middle letter is ignored in this definition (or it belongs to both halves). For example, the word RESTAURATEURS balances two identical sets of letters on either side of the central R. To determine if two strings contain exactly the same letters, but not necessarily in the same order, you can traverse the letters of the first string one by one, and try to cancel them in the second string. If this works for all letters, both strings contain the same letters.

Your task:

-

Write a function ouroboros that takes a word that only contains letters. The function must return a Boolean value that indicates whether or not the given word is an ouroboros.

-

Write a function tsuchinoko that takes a word or a sentence. The function must return the number of letters in the given word or sentence that occupy the same position as in the alphabet. In determining the positions we only take into account the letters, the other characters in the sentence (that are no letters) must be ignored.

-

Write a function amphisbaena that takes a word that only contains letters. The function must return a Boolean value that indicates whether or not the given word is an amphisbaena.

All of these functions should work case insensitive (no distinction between uppercase and lowercase letters).

Example

>>> ouroboros('agaragar')

True

>>> ouroboros('sensuousnesses')

True

>>> ouroboros('tattarrattat')

False

>>> tsuchinoko('Archetypical')

5

>>> tsuchinoko('RESTAURATEURS')

0

>>> tsuchinoko('recherche')

3

>>> tsuchinoko('A bad egg hit KLM wipers two ways.')

16

>>> amphisbaena('RESTAURATEURS')

True

>>> amphisbaena('Archetypical')

False

>>> amphisbaena('recherche')

True

Resources

-

Benfey OT (1958). August Kekulé and the Birth of the Structural Theory of Organic Chemistry in 1858. Journal of Chemical Education 35, 21-23. 4

-

Gilles J (1966). Auguste Kekulé et son oeuvre, réalisée a Gand de 1858 à 1867. Memoires de l'Académie Royale de Belgique 37, 1-40.

-

Kekulé A (1890). Benzolfest Rede. Berichte der Deutchen Chemischen Gesellschaft 23(1), 1302-1311. 5

-

Moss R (2010). The Secret History of Dreaming. New World Library. 6

-

Read J (1957). From Alchemy to Chemistry. Courier Corporation.7

-

Rocke AJ (2010). Image and Reality: Kekulé, Kopp and the Scientific Imagination. University of Chicago Press. 8