In Chapter

21

I gave the example of Apple and Orange both being subclasses of a

class Fruit, and Student and Teacher both being subclasses of a

class Person. You can implement such a hierarchy of classes and

subclasses using “inheritance.”

Basically, inheritance is really simple. When you define a new class, between parentheses you can specify another class. The new class inherits all the attributes and methods of the other class, i.e, they are automatically part of the new class.

class Person:

def __init__( self, firstname, lastname, age ):

self.firstname = firstname

self.lastname = lastname

self.age = age

def __repr__( self ):

return "{} {}".format( self.firstname, self.lastname )

def underage( self ):

return self.age < 18

class Student( Person ):

pass

albert = Student( "Albert", "Applebaum", 19 )

print( albert )

print( albert.underage() )

As you can see, the Student class inherits all properties and methods

of the class Person.

Extending and overriding

To extend a subclass with new methods, you can just define the new methods for the subclass. If you define methods that already exist in the parent class (or “superclass”), they “override” the parent class methods, i.e., they use the new method as specified by the subclass.

Often, when you override a method, you still want to use the method of

the parent class. For instance, if the Student class needs a list of

courses in which the student is enrolled, the course list must be

initialized as an empty list in the __init__() method. Yet if I

override the __init__() method, the student’s name and age are no

longer initialized, unless I make sure that they are. You can make a

copy of the __init__() method for Person into Student and adapt

that copy, but it is better to actually call the __init__() method of

Person inside the __init__() method of Student. That way, should

the __init__() method of Person change, there is no need to update

the __init__() method of Student.

There are two ways of calling a method of another class: by using a

“class call,” or by using the super() method.

A class call entails that a method is called using the syntax

<classname>.<method>(). So, to call the __init__() method of

Person, I can write Person.__init__(). I am not limited to calling

methods of the superclass this way; I can call methods of any class.

Since such a call is not a regular method call, you have to supply

self as an argument. So, for the code above, to call the __init__()

method of Person from the __init__() method of Student, you write

Person.__init__( self, firstname, lastname, age ) (I am allowed to use

self here because every instance of Student is also an instance of

Person, as Student is a subclass of Person).

Using super() means that you can directly refer to the superclass of a

class by using the standard function super(), without knowing the name

of the superclass. So to call the __init__() method of the superclass

of Student, I can write super().__init__(). You do not supply self

as the first argument if you use super() like this. So, for the code

above, to call the __init__() method of Person from the __init__()

method of Student, you write

super().__init__( firstname, lastname, age ).

Of these two approaches, I prefer the use of super(), but only in this

specific way: to call the immediate superclass in single-class

inheritance. super() can be called in different ways and has a few

intricacies, which I will get to below.

In the code below, the class Student gets two new attributes: a

program and a course list. The method __init__() gets overridden to

create these new attributes, but also calls the __init__() method of

Person. Student gets a new method, enroll(), to add courses to the

course list. Finally, as a demonstration I overrode the method

underage() to make students underage when they are not 21 yet (sorry

about that).

class Person:

def __init__( self, firstname, lastname, age ):

self.firstname = firstname

self.lastname = lastname

self.age = age

def __repr__( self ):

return "{} {}".format( self.firstname, self.lastname )

def underage( self ):

return self.age < 18

class Student( Person ):

def __init__( self, firstname, lastname, age, program ):

super().__init__( firstname, lastname, age )

self.courselist = []

self.program = program

def underage( self ):

return self.age < 21

def enroll( self, course ):

self.courselist.append( course )

albert = Student( "Albert", "Applebaum", 19, "CSAI" )

print( albert )

print( albert.underage() )

print( albert.program )

albert.enroll( "Methods of Rationality" )

albert.enroll( "Defense Against the Dark Arts" )

print( albert.courselist )

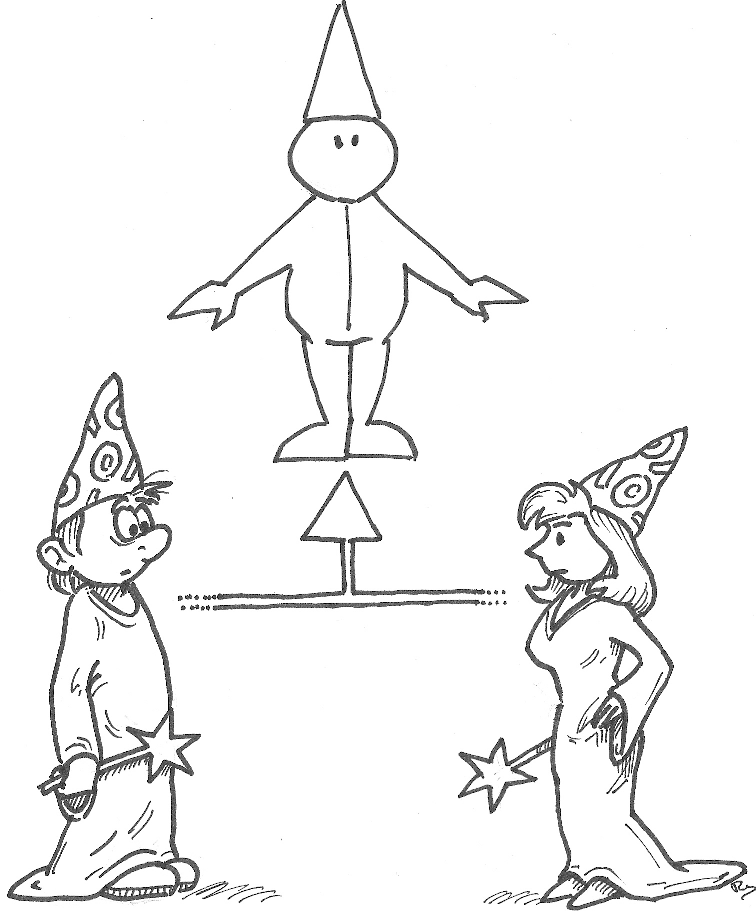

Multiple inheritance

You can create a class that inherits from multiple classes. This is called “multiple inheritance.” You specify all the superclasses, with commas in between, between the parentheses of the class definition. The new class now forms a combination of all the superclasses.

When a method is called, to decide which method implementation to use, Python first checks whether it exists in the class for which the method is called itself. If it is not there, it checks all the superclasses, from left to right. As soon as it finds an implementation of the method, it will execute it.

If you want to call a method from a superclass, you have to tell Python

which superclass you wish to call. You best do that directly with a

class call. However, you can use super() for this too, but it is

pretty tricky. You provide the order in which the classes should be

checked as arguments to super(). However, the first argument is not

checked by super() (I assume that it is supposed to be self).

It is something like this: You have three classes, A, B, and C. You

create a new class D which inherits from all other three classes, by

defining it as class D( A, B, C ). When in the __init__() method of

D you want to call the __init__() methods of the three parent classes,

you can call them using class calls as A.__init__(), B.__init__(),

and C.__init__(). However, if you want to call the __init__() method

of one of them, but you do not know exactly which, but you do know the

order in which you want to check them (for instance, B, C, A), then you

can call super() with self as the first argument and the other three

classes following it in the order in which you want to check them (for

instance, super( self, B, C, A ).__init__()).

As I said, it is pretty tricky. Multiple inheritance is tricky anyway. My general recommendation is that you do not use it, unless there is really no way around it. Many object oriented languages do not even support multiple inheritance, and those that do tend to warn against using it.

So I am not even going to give an example of using multiple inheritance, and neither am I going to supply exercises for multiple inheritance. You should simply avoid using it, until you have a lot of experience with Python and object oriented programming. And by that time, you probably see ways of constructing your programs that do not need multiple inheritance at all.