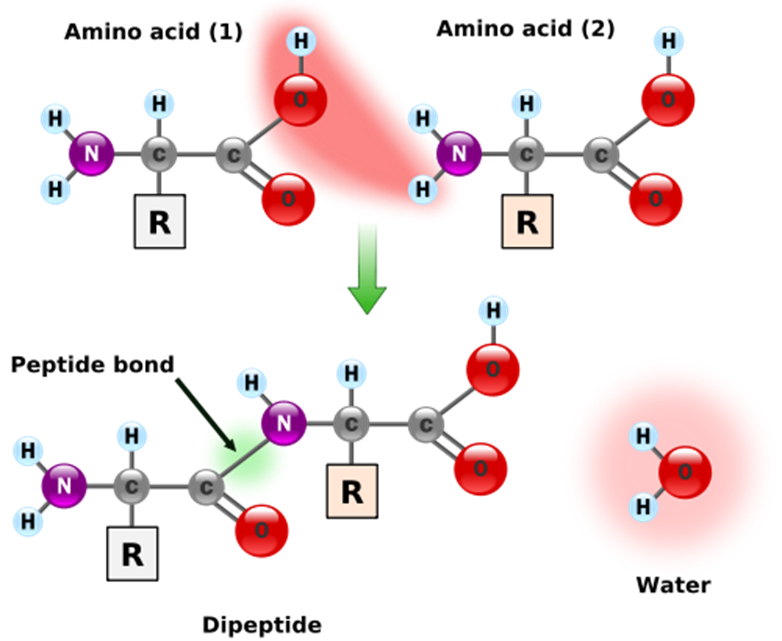

When two amino acids link together, they form a peptide bond, which releases a molecule of water (left figure). Thus, after a series of amino acids have been linked together into a polypeptide, every pair of adjacent amino acids has lost one molecule of water, meaning that a polypeptide containing $$n$$ amino acids has had $$n-1$$ water molecules removed.

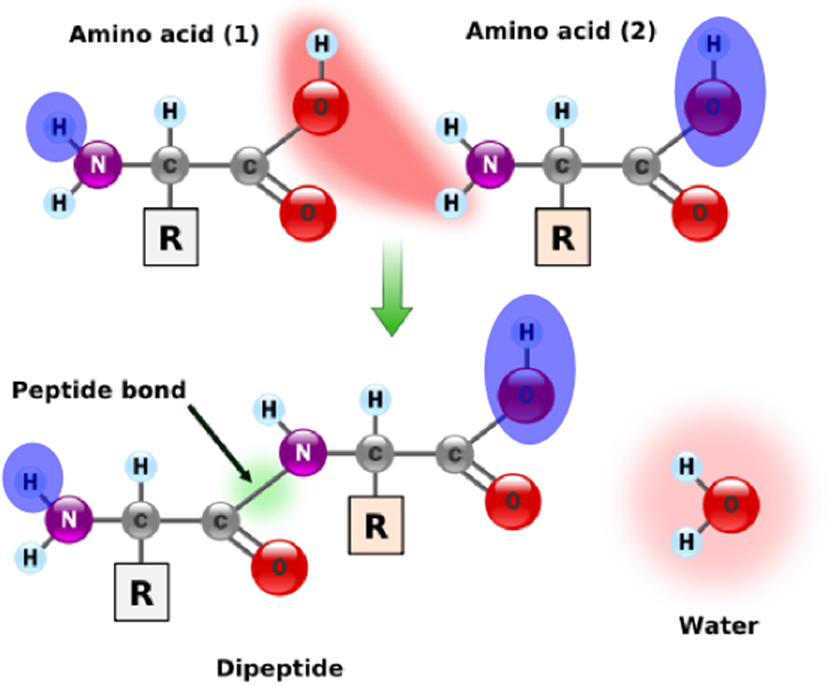

More generally, a residue is a molecule from which a water molecule has been removed. Every amino acid in a protein are residues except the leftmost and the rightmost ones. These outermost amino acids are special in that one has an "unstarted" peptide bond, and the other has an "unfinished" peptide bond. Between them, the two molecules have a single "extra" molecule of water (see the atoms marked in blue in the figure on the right). Thus, the mass of a protein is the sum of masses of all its residues plus the mass of a single water molecule.

There are two standard ways of computing the mass of a residue by summing the masses of its individual atoms. Its monoisotopic mass is computed by using the principal (most abundant) isotope of each atom in the amino acid, whereas its average mass is taken by taking the average mass of each atom in the molecule (over all naturally appearing isotopes).

Many applications in proteomics rely on mass spectrometry, an analytical chemical technique used to determine the mass, elemental composition, and structure of molecules. In mass spectrometry, monoisotopic mass is used more often than average mass, and so all amino acid masses are assumed to be monoisotopic unless otherwise stated.

The standard unit used in mass spectrometry for measuring mass is the atomic mass unit, which is also called the dalton (Da) and is defined as one twelfth of the mass of a neutral atom of carbon-12. The mass of a protein is the sum of the monoisotopic masses of its amino acid residues plus the mass of a single water molecule (whose monoisotopic mass is 18.01056 Da).

In some applications of mass spectrometry, the complication of having to distinguish between residues and non-residues is avoided by only considering peptides excised from the middle of the protein. This is a relatively safe assumption because in practice, peptide analysis is often performed in tandem mass spectrometry. In this special class of mass spectrometry, a protein is first divided into peptides, which are then broken into ions for mass analysis.

Assignment

To calculate the mass of a given protein, you have to implement the following functions:

-

A function mass_table that takes the location (str) of a text file. Each line of this text file should contain an uppercase letter, followed by one or more spaces and a real-valued number. All uppercase letters in the file must be distinct and represent the different amino acids. The read-valued numbers represent the monoisotopic mass of the amino acid on the same line. The function must return a dictionary (dict) that maps each amino acid (str) in the given file onto its monoisotopic mass (float).

-

A function protein_mass that takes two arguments: a protein sequence and a mass table. The protein sequence is given as a string (str) that only contains uppercase letters, representing the amino acid sequence of the protein. The mass table is represented as a dictionary (dict) that maps each upper case letter (str) that is used to represent an amino acid onto its monoisotopic mass (float). In addition, the function has an optional parameter peptide (bool) that indicates whether the given protein sequence represents a peptide that was excised from the middle of a protein (default value: False). The function must return the mass (float) of the given protein sequence.

Example

In the following interactive session, we assume that the text file mass.txt1 is located in the current directory.

>>> table = mass_table('mass.txt2')

>>> table['A']

71.03711

>>> table['E']

129.04259

>>> protein_mass('SKADYEK', table)

839.40248

>>> protein_mass('SKADYEK', table, peptide=True)

821.3919199999999