There are three extra statements that help you control the flow in a

loop. They are else, break, and continue. They work with both

while and for loops.

else

Just like with an if statement, you can add an else statement to the

end of a while or for loop. The code block for the else is

executed whenever the loop ends, i.e., when the boolean expression for

the while loop evaluates to False, or when the last item of the

collection of the for loop is processed. Here is an example for a

while loop:

i = 0

while i < 5:

print( i )

i += 1

else:

print( "The loop ends, i is now", i )

print( "Done" )

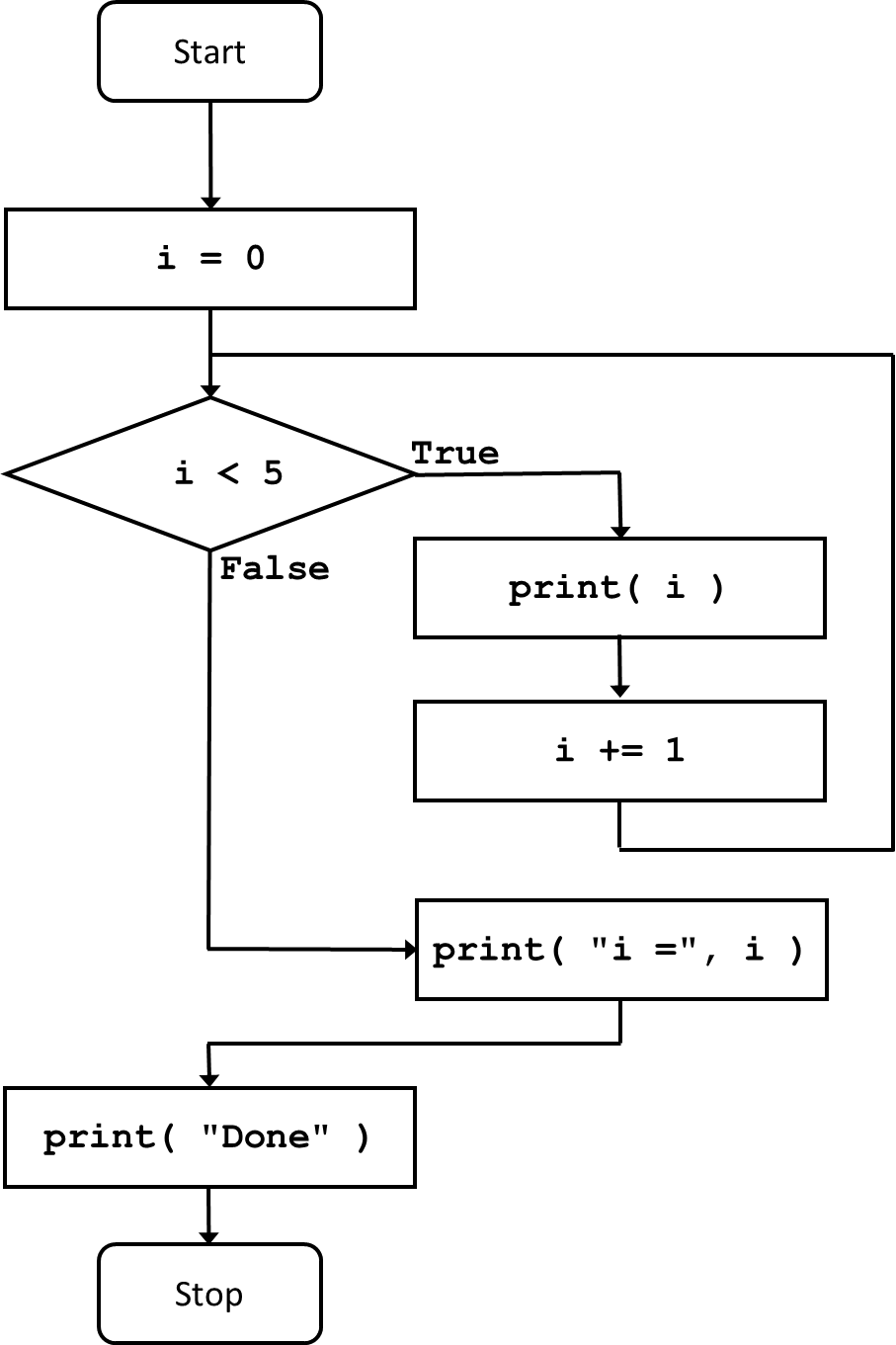

This code is equivalent to the flow chart in Figure

8.21.

When you look at the flow chart you might think it does not make much

sense to use an else, but it can be powerful when combined with a

break (which follows next).

Here is an example of using else for a for loop:

for fruit in ( "apple", "orange", "strawberry" ):

print( fruit )

else:

print( "The loop ends, fruit is now", fruit )

print( "Done" )

Notice that after the while loop above, the value of i is 5. The

value of fruit after the for loop above is the last item that it

encountered, i.e., "strawberry".

break

The break statement allows you to break out of a loop prematurely.

I.e., when Python encounters the break statement, it will no longer

process the remainder of the code block for the loop, and will not loop

back to the loop’s first line. It will simply continue with the first

statement after the loop’s code block.

To see why this is useful, here follows an interesting exercise. I am looking for a number that starts with a 1, and when you transfer that 1 to the end of the number, the result is a number that is three times as high. For example, if I check the number 1867, I move the 1 from the start to the end, which gives 8671. If 8671 would be three times 1867, that is the answer I seek. It is not, so 1867 is not correct. The code to solve this is actually fairly short, and gives the lowest number for which the comparison holds:

i = 1

while i <= 1000000:

num1 = int( "1" + str( i ) )

num2 = int( str( i ) + "1" )

if num2 == 3 * num1:

print( num2, "is three times", num1 )

break

i += 1

else:

print( "No answer found" )

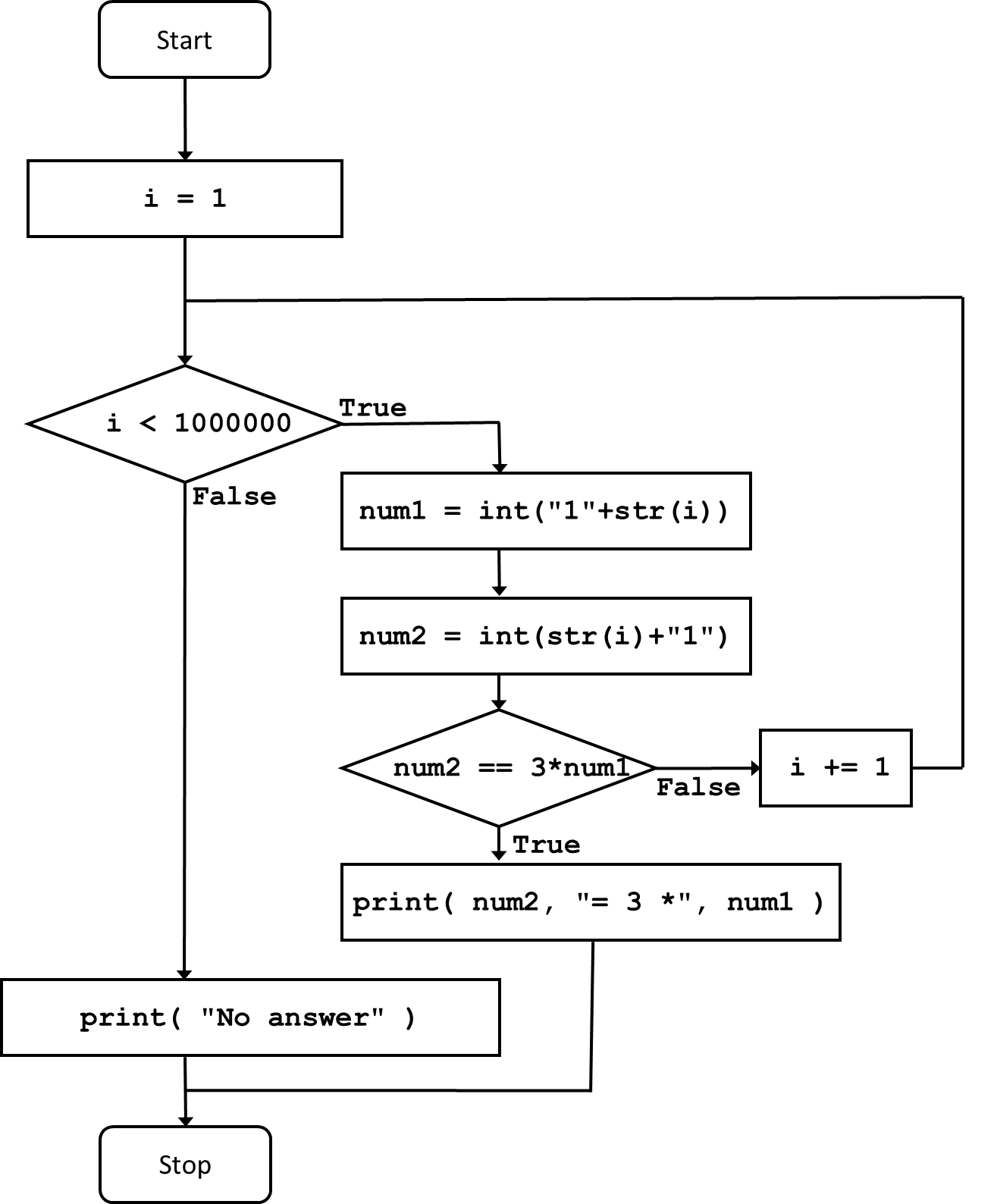

This code is expressed by the flow chart in Figure 8.32.

In this example you see the break statement used to good effect. Since

I have no idea which number I am looking for, I am just going to check a

whole bunch of numbers. I let a counter i run up to 1000000. Of

course, I don’t know if I find the answer before i has reached

1000000, but I should set a limit somewhere, because I don’t know if a

number with the requested property exists at all, and I do not want to

create an endless loop. I might find the answer at any point, and when I

do, I break out of the loop, because further testing of numbers no

longer serves a purpose.

The point here is that the setting of the maximum value of i to

1000000 is not because I know that I have to generate one million

numbers. I have no idea how many times I have to cycle through the loop.

I just know that if I encounter the requested number at some point, I am

done and can skip the remainder of the cycles. That is exactly what the

purpose of the break is.

With some juggling the boolean expression for the loop actually can do

the comparison for me. It would be something like

while (i < 1000000) and (num1 != 3*num2):. This becomes a bit

convoluted, and I would also have to give num1 and num2 starting

values before the loop starts. Still, it is always possible to avoid

using a break, but applying the break might make code more readable

and flow better, as it does in this case.

The break statement cannot be used outside a loop. It is only defined

for loops. (Take note of this. I very often see students putting break

statements in conditions that are not inside a loop, and then look

mystified when Python reports a runtime error.)

Note that when a break statement is encountered, and the loop also has

an else clause, the code block for the else will not be executed.

I use this to good effect in the code above, by ensuring that the text

that indicates that no answer is found, only will be printed if the loop

ends by checking all the numbers without finding an answer.

The following code checks a list of grades for a student. As long as all

grades are 5.5 or higher, the student passes. When one or more grades

are lower than 5.5, the student fails. The grades are in a collection

that is given to a for loop.

for grade in ( 8, 7.5, 9, 6, 6, 6, 5.5, 7, 5, 8, 7, 7.5 ):

if grade < 5.5:

print( "The student fails!" )

break

else:

print( "The student passes!" )

Run the code above and notice that the student fails. Then remove the 5 from the list of grades and notice that the student now passes.

continue

When the continue statement is encountered in the code block of a

loop, the current cycle ends immediately and the code loops back to the

start of the loop. For a while loop, that means that the boolean

expression is evaluated again. For a for loop, that means that the

next item is taken from the collection and processed.

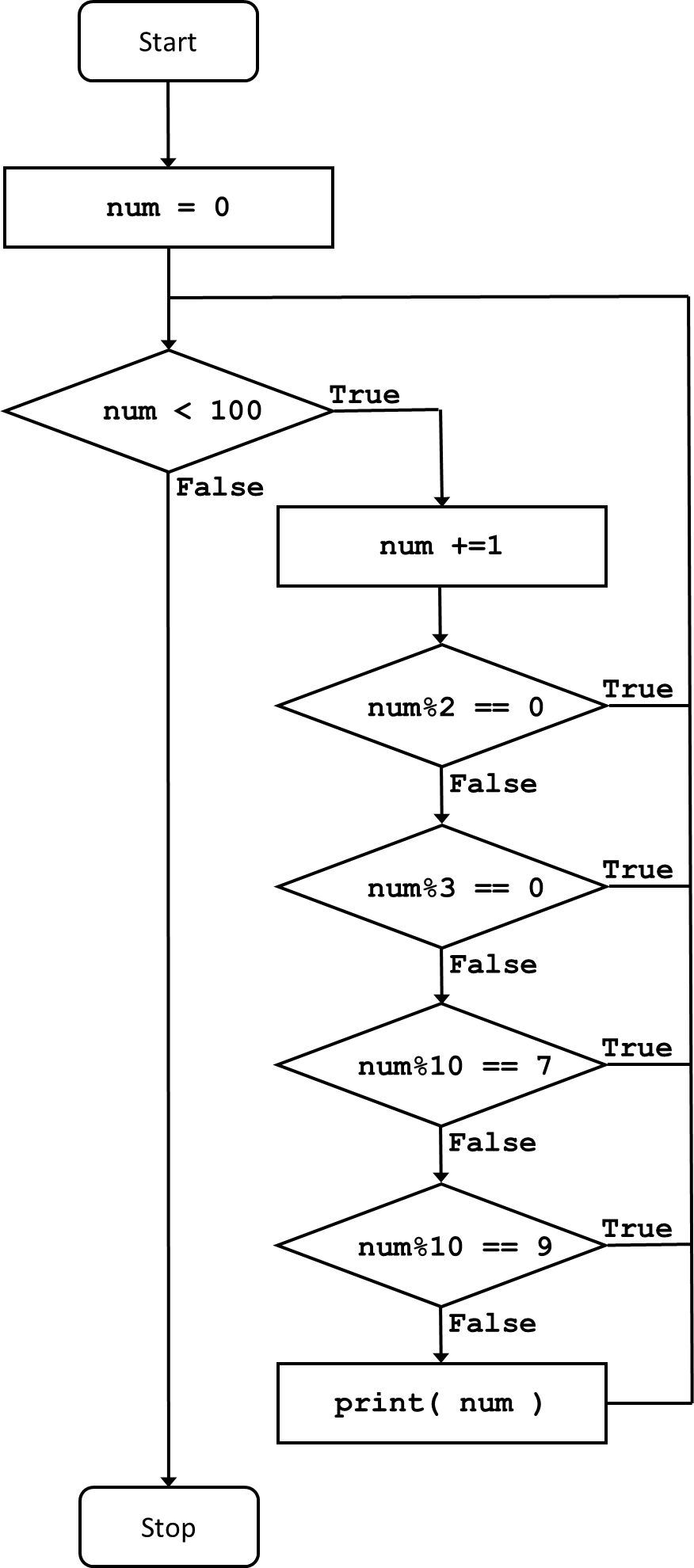

The following code prints all numbers between 1 and 100 that cannot be divided by 2 or 3, and do not end in a 7 or 9.

num = 0

while num < 100:

num += 1

if num%2 == 0:

continue

if num%3 == 0:

continue

if num%10 == 7:

continue

if num%10 == 9:

continue

print( num )

This code is also expressed by the flow chart in Figure 8.53.

I don’t know why you would want this list, but the use of continue

statements to implement it helps. Alternatively, you could have created

one big boolean expression for an if statement, but that would become

unreadable quickly. Still, just like break statements, continue

statements can always be avoided if you really want to, but they do help

keeping code understandable.

Note that continue statements, just like break statements, can only

be used inside loops.

Be very, very careful when using a continue in a while loop. Most

while loops use a number that restricts the number of cycles through

the loop. Usually such a number is increased at the bottom of the code

block for the loop. A continue statement would loop back to the

boolean expression immediately, without increasing the number, and thus

such a continue could easily cause an endless loop. I.e.:

i = 0

while i < 10:

if i == 5:

continue

i += 1

causes an endless loop!

Write a program that processes a collection of numbers using a for

loop. The program should end immediately, printing only the word “Done,”

when a zero is encountered (use a break for this). Negative numbers

should be ignored (use a continue for this; I know you can also do

this with a condition, but I want you to practice with continue). If

no zero is encountered, the program should display the sum of all

numbers (do this in an else clause). Always display “Done” at the end

of the program. Test your program with the collection

( 12, 4, 3, 33, -2, -5, 7, 0, 22, 4 ). With these numbers, the program

should display only “Done.” If you remove the zero, it should display 85

(and “Done”).