Conditional statements are, as the introduction to this chapter said,

statements consisting of a test and one or more actions, whereby the

actions only get executed if the test evaluates to True. Conditional

statements are also called “if-statements,” as they are written using

the special keyword if.

Here is an example:

x = 5

if x == 5:

print( "x equals 5" )

The syntax of the if statement is as follows:

if <boolean expression>:

<statements>

Note the colon (:) after the boolean expression, and the fact that

<statements> is indented.

Code blocks

In the syntactic description of the if statement above, you see that

the <statements> are “indented,” i.e., they are placed one tabulation

to the right. This is intentional and necessary. Python considers

statements that are following each other and that are at the same level

of indentation part of a code block. The code block underneath the first

line of the if statement is considered to be the list of actions that

are executed when the boolean expression evaluates to True. For

example:

x = 7

if x < 10:

print( "This line is only executed if x < 10." )

print( "And the same holds for this line." )

print( "This line, however, is always executed." )

Change the value of x to see how it affects the outcome of the code.

Thus, all the statements under the if that are indented, belong to the

code block that is executed when the boolean expression of the if

statement evaluates to True. This code block is skipped if the boolean

expression evaluates to False. Statements which follow the if

construction which are not indented (as deep as the code block under the

if), are executed, regardless of whether the boolean expression

evaluates to True or False.

Naturally, you are not restricted to having just a single if statement in your code. You can have as many as you like.

x = 5

if x == 5:

print( "x equals 5" )

if x > 4:

print( "x is greater than 4" )

if x >= 5:

print( "x is greater than or equal to 5" )

if x < 6:

print( "x is less than 6" )

if x <= 5:

print( "x is less than or equal to 5" )

if x != 6 :

print( "x does not equal 6" )

Again, try changing the value of x and see how it affects the outcome.

Indentation

In Python, correct indenting is of the utmost importance! Without correct indentation, Python will not be able to recognize which statements belong together as one code block, and therefore cannot execute your code correctly.11

Note that you can indent using the Tab key, or indent using spaces.

Most editors will auto-indent for you, i.e., if, for instance, you write

the first line of an if statement, once you press Enter to go to the

next line, it will automatically “jump in” one level of indentation (if

it does not, it is very likely that you forgot the colon at the end of

the conditional expression). Also, when you have indented one line to a

certain level of indentation, the next line will use the same level. You

can get rid of indentations using the Backspace key.

For Python programs, a normal level of indentation is four spaces, i.e.,

one press of the Tab key should “jump in” four spaces. As long as you

are in one editor, you can in such a case either use the Tab key, or

press the spacebar four times, to go up one indentation level. So far so

good. You may get into problems, however, if you port your code to

another editor, which might have a different setting for the Tab key.

If you edit your code in a such a different editor, even though it might

look okay, Python may see that there are indentation conflicts (a mix of

tabulations and space-indentations) and may report a syntax error when

you try to run your code. Most editors therefore offer the option to

automatically replace tabulations with spaces, so that such problems do

not arise. If you use a text editor to write Python code, check if it

contains such an option, and if so, ensure that tabulations are set to 4

and are automatically replaced by spaces.

The following code contains multiple indentation errors. Fix them all.

# This code contains indentation errors!

x = 3

y = 4

if x == 3 and y == 4:

print( "x is 3" )

print( "y is 4" )

if x > 2 and y < 5:

print( "x > 2" )

print( "y < 5" )

if x < 4 and y > 3:

print( "x < 4" )

print( "y > 3" )

Two-way decisions

Often a decision branches, e.g., if a certain condition arises, you want

to take a particular action, but if it does not arise, you want to take

another action. This is supported by Python in the form of an expansion

to the if statement that adds an else branch.

x = 4

if x > 2:

print( "x is bigger than 2" )

else:

print( "x is smaller than or equal to 2" )

The syntax is as follows:

if <boolean expression>:

<statements>

else:

<statements>

Note the colon (:) after both the boolean expression and the else.

It is important that the word else is aligned with the word if that

it belongs to. If you do not align them correctly, this results in an

indentation error.

A consequence of adding an else branch to an if statement is that

always exactly one of the two code blocks will be executed. If the

boolean expression of the if statement evaluates to True, the code

block directly under the if will be executed, and the code block

directly under the else will be skipped. If it evaluates to False,

the code block directly under the if will be skipped, while the code

block directly under the else will be executed.

You can test whether an integer is odd or even using the modulo

operator. Specifically, when x % 2 equals zero, then x is even, else

it is odd. Write some code that asks for an integer and then reports

whether it is even or odd (you can use the getInteger() function from

pcinput to ask for an integer).

Note: As far as indentation is concerned, it is not absolutely necessary

to have the code block under the else branch use the same number of

spaces in indentation as the code block under the if branch, as long

as the indentation is consistent within the code block. However,

accomplished programmers use consistent indentation throughout their

programs, which makes it easier to see what the whole if-else

statement encompasses. For example, in the code below the indentation in

the else branch uses less spaces than the indentation in the if

branch. While syntactically correct, this makes the code less readable.

# Example of syntactically correct but ugly indenting.

x = 1

if x > 2:

print( "x is bigger than 2" )

else:

print( "x is smaller than or equal to 2" )

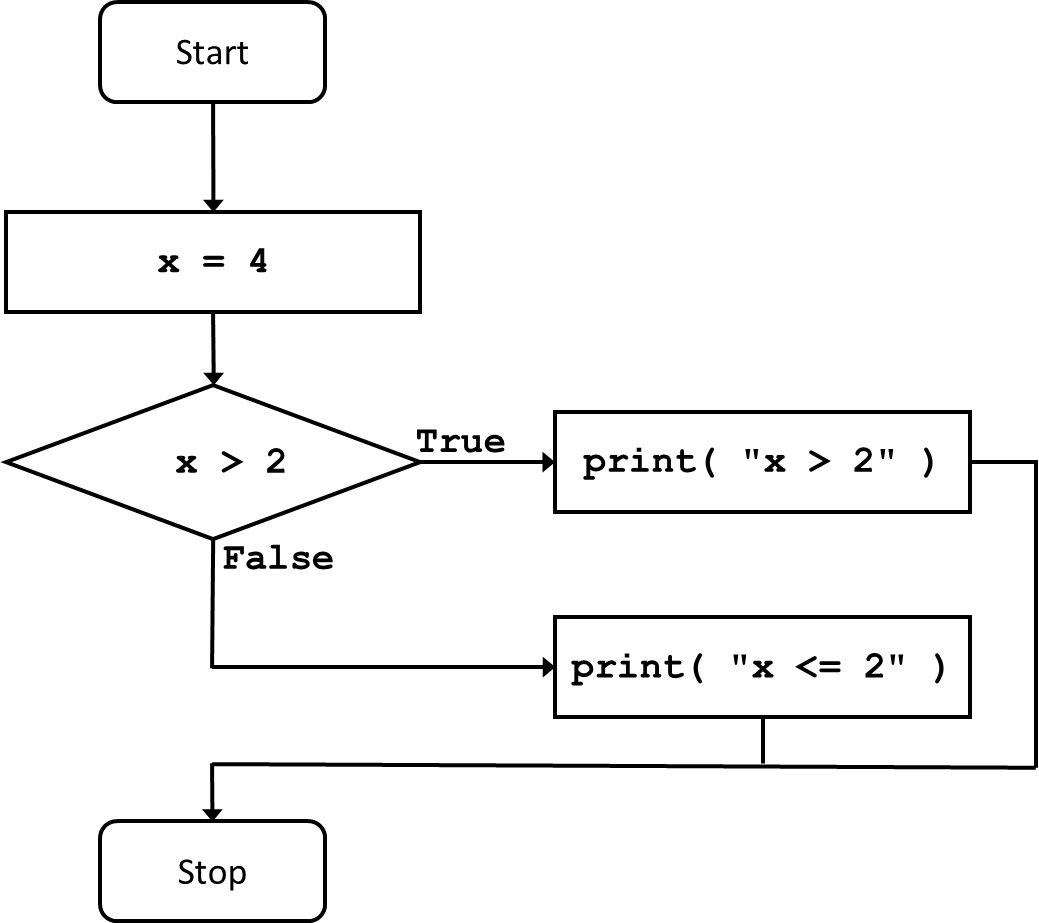

Flow charts

In the early days of programming, programmers often expressed the algorithms they wanted to implement by means of so-called “flow charts.” Nowadays, flow charts are seldom used anymore. However, I found that it often helps students understanding how exactly conditions (and, for the next chapter, iterations) work if they are shown a flow chart of the process.

A flow chart is a diagram that shows different kinds of blocks with

arrows in between. The blocks are of three kinds (at least, that is all

I need for this book). Rectangular blocks contain statements that are

executed. Diamond-shaped blocks contain a condition that evaluates to

either True or False. Rectangular blocks with rounded corners

indicate either the start (using the text “Start”) or end (using the

text “Stop”) of the algorithm.

To interpret a flow chart, you begin at the “Start” block, and follow

the arrows, executing all statements that you encounter. When you get to

a diamond-shaped block, you evaluate the condition in it, and then

either follow the arrow marked True in case it evaluates to True, or

the arrow marked False when it evaluates to False. When you

encounter the “Stop” block, you are finished.

For example, the code shown above, that checks if a number is greater than 2 or smaller than or equal to 2, and prints some text that states as much, is equivalent to the flow chart shown in Figure 7.12.

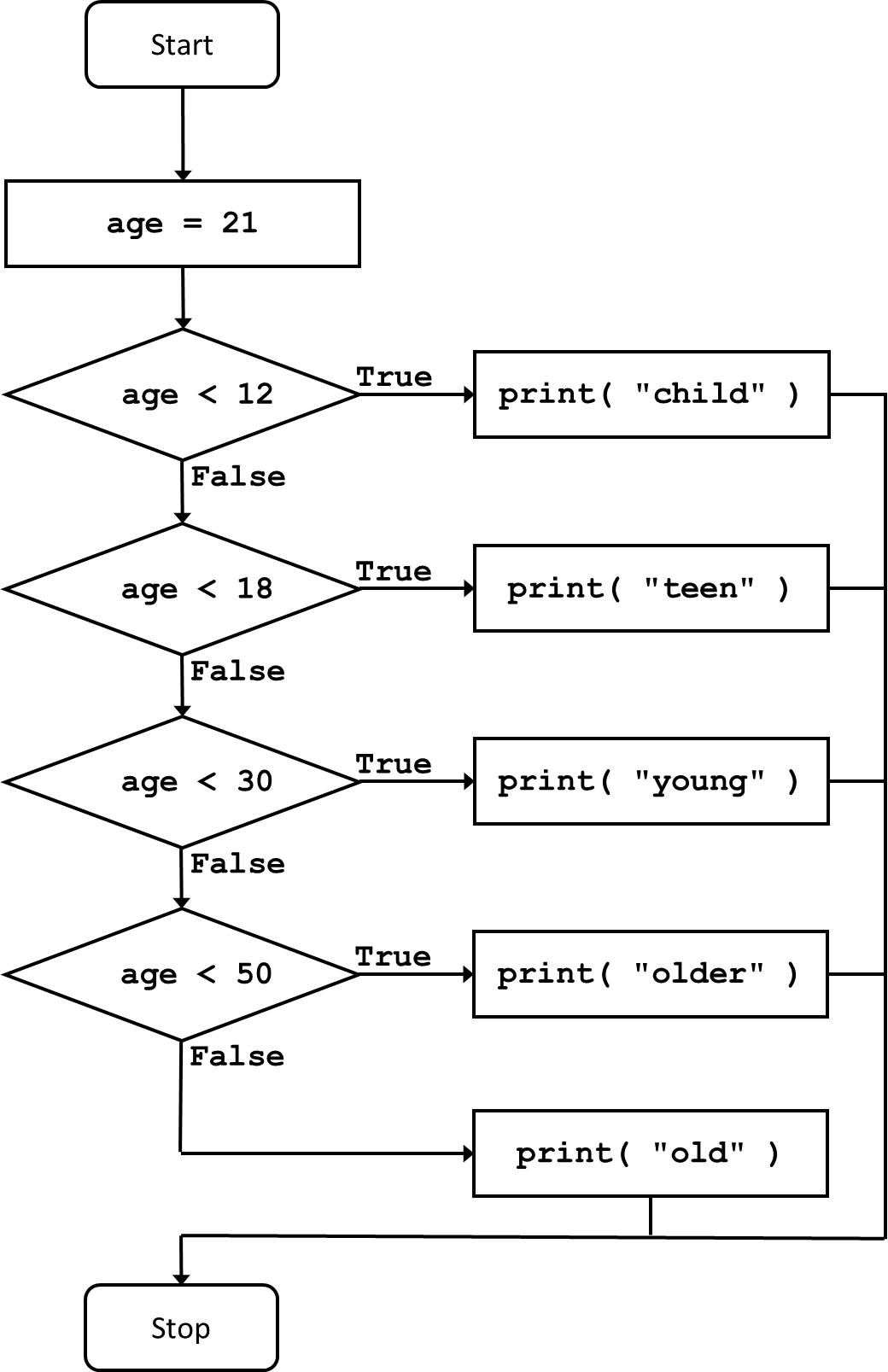

Multi-branch decisions

Occasionally, you encounter multi-branch decisions, where one of

multiple blocks of commands has to be executed, but never more than one

block. Such multi-branch decisions can be implemented using a further

expansion of the if statement, namely in the form of one or more

elif statements (elif stands for “else if”).

age = 21

if age < 12:

print( "You're still a child!" )

elif age < 18:

print( "You are a teenager!" )

elif age < 30:

print( "You're pretty young!" )

elif age < 50:

print( "Wisening up, are we?" )

else:

print( "Aren't the years weighing heavy?" )

This code is equivalent to the algorithm expressed by the flow chart in Figure 7.33.

In the code block above, change age to different values and observe the results.

The syntax is as follows:

if <boolean expression>:

<statements>

elif <boolean expression>:

<statements>

else:

<statements>

The syntax above shows only one elif, but you can have multiple. The

different tests in an if-elif-else construct are executed in

order. The first boolean expression that evaluates to True will cause

the code block that belongs to that expression to be executed. None of

the other code blocks of the construct will be executed.

So, first the boolean expression next to the if will be evaluated. If

it evaluates to True, the code block underneath the if will be

executed. Otherwise, the boolean expression for the first elif will be

evaluated. If that turns out to be True, the code block underneath it

will be executed. Otherwise, the boolean expression for the next elif

will be evaluated. Etcetera. Only when the boolean expressions for the

if and all of the elifs evaluate to False, the code block

underneath the else will be executed.

Therefore, in the code above, you do not need to test

age >= 12 and age < 18 for the first elif. Just testing age < 18

suffices, because if age was smaller than \(12\), already the boolean

expression for the if would have evaluated to True, and the boolean

expression for the first elif would not even have been encountered by

Python.

Note that the inclusion of the else branch is always optional.

However, in most cases where I need elifs I include it anyway, if only

for error checking.

Write a program that defines a variable weight. If weight is greater

than \(20\) (kilo’s), print: “There is a $$25 surcharge for luggage that

is too heavy.” If weight is smaller than \(20\), print: “Have a safe

flight!” If weight is exactly \(20\), print: “Pfew! The weight is just

right!” Make sure that you change the value of weight a couple of

times to check whether your code works.

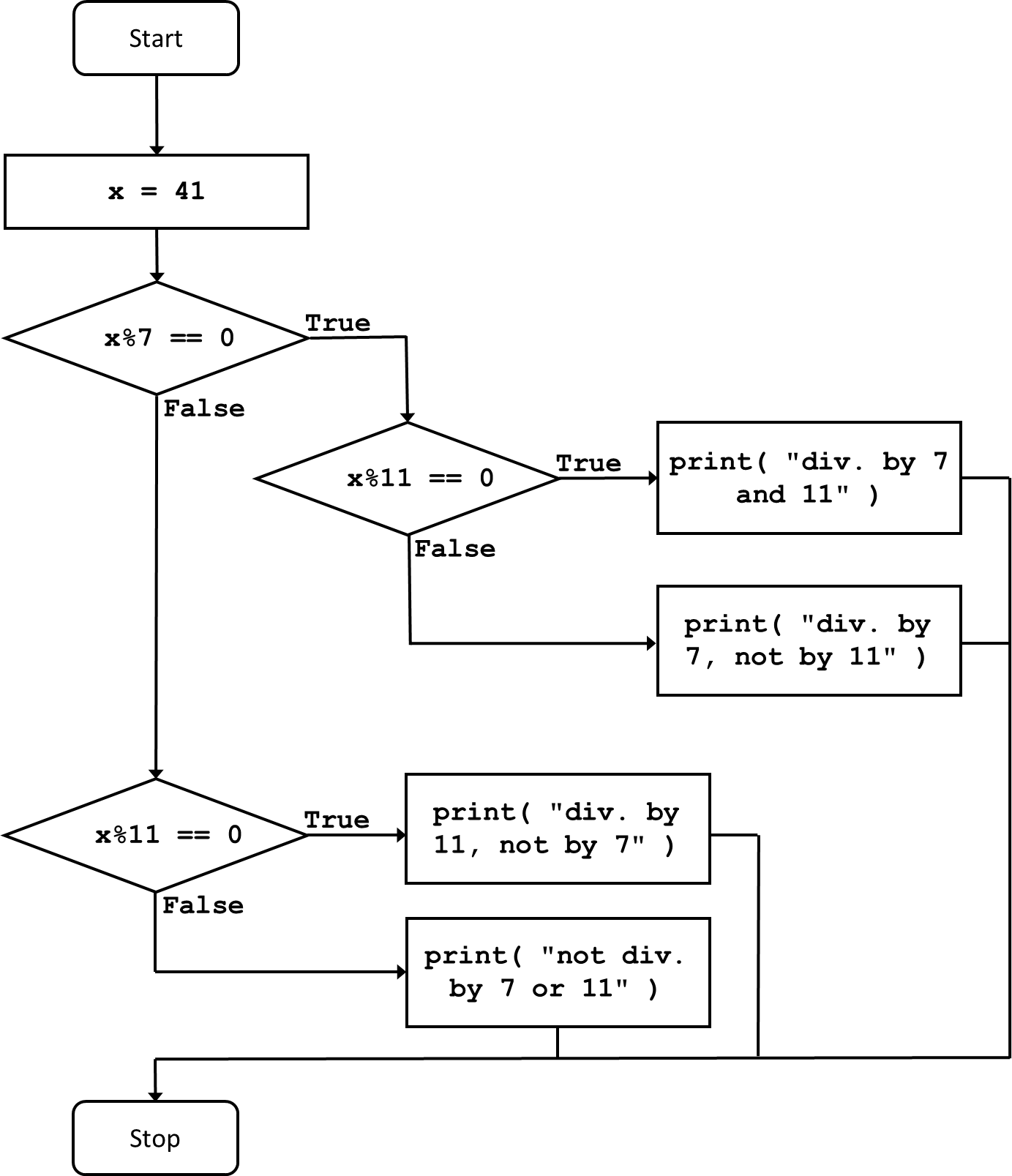

Nested conditions

Given the rules of the if-elif-else statements and identation, it

is perfectly possible to use an if statement within another if

statement. This second if statement is only executed if the condition

for the first if statement evaluates to True, as it belongs to the

code block of the first if statement. This is called “nesting.”

x = 41

if x%7 == 0:

# --- Here starts a nested block of code ---

if x%11 == 0:

print( x, "is dividable by both 7 and 11." )

else:

print( x, "is dividable by 7, but not by 11." )

# --- Here ends the nested block of code ---

elif x%11 == 0:

print( x, "is dividable by 11, but not by 7." )

else:

print( x, "is dividable by neither 7 nor 11." )

This code is equivalent to the algorithm expressed in Figure 7.44.

Change the value of x and observe the results.

Note that the example above is just to illustrate nesting; you probably

already know different ways of getting the same results that are a bit

more readable. In particular, nesting of if statements can often be

avoided by judicious use of elifs. To give an example, here is a

“nested” example of the age code given above:

age = 21

if age < 12:

print( "You're still a child!" )

else:

if age < 18:

print( "You are a teenager!" )

else:

if age < 30:

print( "You're pretty young!" )

else:

if age < 50:

print( "Wisening up, are we?" )

else:

print( "Aren't the years weighing heavy?" )

I assume you agree that the version with the elifs looks better.

-

In many programming languages (actually, in almost all programming languages), code blocks are recognized by having them start and end with a specific symbol or keyword. For instance, in languages such as Java and C++, code blocks are enclosed by curly brackets, while in languages such as Pascal and Modula, code blocks are started with the keyword

beginand ended with the keywordend. That means that in almost all languages, indenting to recognize code blocks is not necessary. However, you will find that code written by capable programmers is always nicely indented, regardless of the language. This makes it easy to see which code belongs together, for instance, which commands belong to anifstatement. Python makes indenting a requirement. While for experienced programmers who are new to Python this seems strange at first, they quickly find that they do not care – they were indenting nicely anyway, and Python’s strategy makes that beginning programmers are also required to write nice-looking code. ↩5